Camille Lepage: Photojournalist in Central African Republic dies.

Travelling with the Anti Balaka to Amada Gaza, about 120km from Berberati, we left at 3.30am to avoid the Misca checkpoints and it took us 8 hours by motorbike as there is no proper roads to reach the village. In the region of Amada Gaza, 150 people were killed by the Seleka between March and now. Another attack took place on Sunday killing 6 people, the anti balaka Colonel Rock decides to send his elements there to patrol around and take people who fled to the bush back to their homes safely. #photojournalism #photography #carcrisis #documentary #latergram #antibalaka

Justice for Camille

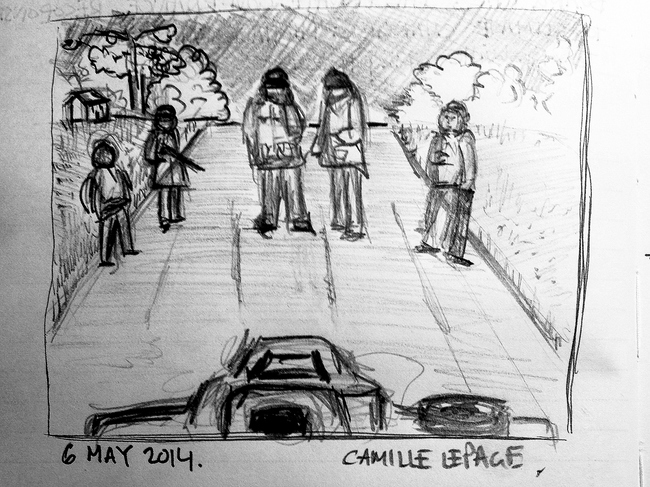

The instagram photo above was the last one taken by Camille Lepage on May 6. On Tuesday, she was found in a car near the Bouar region of Central African Republic. The circumstances of her death are not clear as to whether she was killed or caught in the crossfires but the French Presidency shared the sentiments of the International Federation of Journalism who has released the following statement :

“We appeal for the government of the Central African Republic, as well as the French and other international forces based there, to immediately take every step necessary to find the perpetrators of this appalling act and bring them to swift and full justice.”

But when I think about it, justice is hard to deliver. True, the perpetrators may be the Christian anti-Balaka whose car she was found in or the Muslim rebels who might have ambushed them. But how do you pinpoint blame in a war where both sides have committed injustices they need to answer for ? Camille must have encountered many individuals whose past (and present) actions she would have had to ignore in order to work with them or request their assistance as she documented the crisis. So, even though I understand that those responsible for her death answer for their actions, I can’t help but wonder whether there’s a double standard that the same level of scrutiny, while exercised through rhetoric, isn’t applied for the thousands of innocent civilians who have died and are continuing to die in the crossfires of a murky war. How would Camille see this situation, I wonder.

A war about names

In a recent GQ coverage of the crisis, Ed Caesar called it:

From the outside it looks like a war about competing faiths: Muslim against Christian, the old story. But religion - or at least, theology - is a sideshow. This is not a conflict about contesting interpretations of scripture. There are no crusaders here, no jihadis. Not yet at least. No, this is a war about names - which kinds of names belong in the country, and which do not; about who deserves a name, and who does not. In the Central African Republic, these questions have been answered in blood.

His words were accompanied with graphic images of the grotesque realities of a war about names - mutilated genitals, chopped hands and blood soaked clothes dress the subjects found in these pictures. The photojournalists who are bringing these realities to the front covers for our view do so with the intention of triggering a response strong enough to cause us to demand action. More times than not, it seems our responses are misguided and only seek to redress immediate concerns, rather than seek to understand the long term complexities of these conflicts.

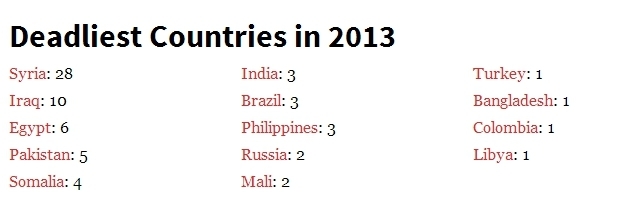

Categorized by year and country

Cases of kidnapped and murdered journalists seem to have almost become a common occurrence. It’s another column of the newspaper we swallow and digest for a short period of time. You only have to visit the Committee to Protect Journalists site where these deaths are listed and categorized by year and country. In 2013 alone, 70 journalists were killed. 23 of them were from Syria making it the deadliest country for media perrsonnel.

Camille will now be an added statistic for the 2014 CPJ reports.

It’s also worth taking a look at the World Press Freedom Index 2014 by Reporters without Borders which ranked CAR at 109, a sharp decline in the list compared to last year due to increased conflict in the region.

As the war broke out in CAR, RWB shared their official recommendations with regards to engagement with media (Dec 2013) :

- the Central African Republic’s media refrain from using a violent or polarizing discourse, that they report the facts without distortion and that they try to defuse tension and promote dialogue in order to prevent further escalation in the violence.

- armed groups stop threatening journalists and respect their status as non-combatants and their role as neutral witnesses of events.

- the transitional authorities continue to encourage the media’s activities so that they can inform the population about political and security developments.

- the international forces deployed in the CAR protect journalist in line with UN Security Council Resolution 1738 on the protection of journalists in conflict zones.

Photojournalists: reckless or fearless ?

Despite the apparent abundance of these news reports of killed journalists which come and go, I couldn’t shrug off Camille’s death for some reason. Maybe it had to do with her body of work online or as simple as having an instagram profile that made our degrees of separation less than they actually are. She was also only 5 years older than me. Two thoughts also came up in trying to explore why I felt this way :

I have been trying to follow the news in CAR actively for the past few months and have been seeing the lack of coverage of the war-torn country. So, I relate to her anger when she shares how “truly frustrating is that the media is indeed not interested!

I was secretly hoping to make things change, but quickly realized it’s going to take longer than I thought. I sincerely hope that once the stories are complete, it would be easier to get them out, if not through media, through books, or perhaps exhibitions.

I admire her persistence and fearlessness in sharing the stories that we need to hear and attempting to draw media attention to the "places in the shadow, where crisis take place but where the media often remain silent”. Her boldness in seeking to find these stories makes it harder for me to digest the tragic circumstances of her death.

Second, as someone who has been intrigued by photojournalism and am considering how to venture into a professional route telling stories through visual mediums, I am troubled by how dangerous it still is for the press to report in regions that don’t enjoy the same level of freedom as countries like Canada where I live currently. The debate of media freedom (considering censorship of scientists talking about environmental research) is another discussion altogether which I will bookmark for a later time.

In trying to understand whether photojournalists are fearless or reckless taking unnecessary risks, here are examples of how professionals in the field see their work:

Tom Stoddart on photojournalism:

Photojournalists are at the front lines of conflict, crime, international emergency and human rights abuses. And no matter how heroic and therefore romanticised these men and women’s jobs may seem to those on the sidelines, the fact of the matter is, photojournalism is a dangerous job – it is not glamorous, likely will not make you a millionaire, and as veteran It sure as hell isn’t sexy.

Fabio Bucciarelli on why he has chosen to speak through images:

I’m using the camera to filter the reality. My way to help the people is documenting what is going on there.

Other notable excerpts are shared from the article “Can a photography really tell the truth?” :

Tom Stoddart: “The bottom line for a photojournalist is truth. If your photographs don’t tell the truth, then it’s a waste of time. […] Photographers are authors, just like writers. The best photojournalists are telling the story through their eyes. Photojournalism isn’t about going and trying to show all sides of a story and trying to be fair to all sides, because that’s impossible.”

Anastasia Taylor-Lind: It’s absolutely ridiculous to believe that photography can be entirely truthful. In photography there is no one truth, no one reality. It’s a 2-Dimensional interpretation by one person of the world around us.

Donald Weber: I think a lot of it is subjective. All you can do is reveal what you can reveal. An image is not necessarily a gospel. To me it’s more important to create a sense of place or to get across an emotional feeling.

Ultimately it comes down to interpretation. However, there are many interpreters to take into account - starting with the photographer taking the image and ending with the many who view the photograph. Interpretation cannot be controlled, thus the truth cannot be expected to be fully defined.

Camille’s own words from an interview in October 2013

What fascinates me about photography is its universal language. Unlike other media, anyone can understand a picture, feel it, it speaks to the viewers. I probably say that as I’m a photographer but I feel that picture you love lives in you, you can think about it and they get you where the photographer was, which is amazing.

I also realized what the media agenda was, and how so many serious stories were missing from the headlines simply because they don’t fit within that agenda, or the advertising company’s interests. I can’t accept that people’s tragedies are silenced simply because no one can make money out of them. I decided to do it myself, and bring some light to them no matter what.

I want the viewers to feel what the people are going through, I’d like them to empathize with them as human beings, rather than seeing them as another bunch of Africans suffering from war somewhere in this dark continent. I wish they think “why on earth are those people in living hell, why don’t we know about it and why is no one doing anything?” I would like the viewers to be ashamed of their government for knowing about it without doing anything to make it end.

The whole moving to South Sudan is an experience by itself, I’ve realized that we don’t need much to live or be happy, simplicity is often more than enough. One important thing is to keep an open heart towards others and what I might not understand — I’m not one to judge, and the best I can do is to learn from each other’s differences. Differences are what makes each of us unique and fascinating.

It’s so frustrating to be covering something so tragic, that no one wants to publish and that can’t see the public light apart from social media.

I think Camille was acutely aware of the dangers that came with her profession and acknowledged that while she couldn’t tell all sides of the story, the voices of those caught in the crossfires of the war in the Central African Republic couldn’t be ignored. Her search for the truth through her lens makes her fearless.

As I began to search for her watermark on photos she had taken, I was taken struck with strong visceral feelings of indignation and guilt when vieweing her ongoing works You Will Forget Me and Vanishing Youth. These emotions stirred and made it painfully clear how I had nothing to offer or do to alleviate their suffering. I was frustrated that my sorrow couldn’t be channeled towards any meaningful benefit for them. Her photos from South Sudan can also be found on the Medecins sans frontieres site. In sharing her experience in CAR, Natalie Roberts, MSF Doctor, wrote

In CAR, people commemorate the dead overnight with drumming. The funeral ground is quite close to the hospital in Bozoum, and close to where we were sleeping, so when there was a death in the hospital we heard drums all night. It doesn’t let you forget that someone has died.

So perhaps in drumming for Camille, we will be drawn to look at her work and use it to focus our attention to instances of injustice and keep each other and our political leaders accountable.

In her 2013 interview, she referenced Ira Glass when discussing the importance of perseverance when trying to tell stories that needed to be heard. What Ira said can be a calling to all those who are where Camille was a few years ago when jumping into her short-lived but impactful career as a photojournalist.

Ira Glass on Storytelling from David Shiyang Liu on Vimeo.